A la conquista del caucho

06.25.16 \ 09.03.16

And we have to become humble in front of this overwhelming misery and overwhelming fornication, overwhelming growth and overwhelming lack of order. Even the stars up here in the sky look like a mess. There is no harmony in the universe. We have to get acquainted to this idea that there is no real harmony as we have conceived it. But when I say this, I say this all full of admiration for the jungle. It is not that I hate it, I love it. I love it very much. But I love it against my better judgment.

Werner Herzog

In looking at objects of Nature while I am thinking, as at yonder moon dim-glimmering thro’ the dewy window-pane, I seem rather to be seeking, as it were asking, a symbolical language for something within me that already and forever exists, than observing anything new. Even when that latter is the case, yet still I have always an obscure feeling as if that new phaenomenon were the dim Awaking of a forgotten or hidden Truth of my inner Nature.

Samuel Coleridge

The opening quote of this text was taken from the documentary Burden of Dreams, where the filmmaker Werner Herzog recounts his experience of living for months in the Peruvian Amazon while filming "Fitzcarraldo," the story of an Irish entrepreneur in the rubber industry and opera lover who intends to build a theater in the middle of the jungle. Herzog's words startle us because they allow us to think of nature as a violent entity: chaotic, obscene and lacking harmony; a strange idea in times like these, where our obsession with the ecological footprint left by humans on the planet has elevated nature to the status of a deity, to then characterize mankind as its main enemy: the stranger who came to, quote, debase it.

This dogmatic stance, aside from exiling humans from the kingdom of nature (thus denying their animality), also forgets that culture and attempts to understand, interpret or give order to the world are inherent in human nature, and loses the perspective that it is thanks to the reciprocity encouraged by these contradictions between nature and culture, between chaos and interpretation, that languages and our most profound expressions have emerged.

This selection of artworks intends to suggest that, if nature is chaotic, it is possible that the languages created by man to represent it, narrate it, rebuild it or deny it, are nothing more than sometimes humble, useless, or deeply delusional attempts to sort, select and interpret chaos.

Buscando Patrones [Seeking Patterns] by Rodolfo Diaz Cervantes, for example, calls on the construction of a fictitious geometry by establishing random patterns in the image of a flock of chickens or a pair of landscapes, while Sin título (SEBEC) [Untitled (Prospection in SEBEC)] is a piece that presents fake meteorites made of plaster by students from a school in Culiacan, Sinaloa in Mexico. For this project, Fritzia Irizar asked the students to recall and reproduce the shape of Bacubirito, a meteorite that fell near the city (1863) and that is now displayed as a monument. By presenting false meteorites that emulate the scientific methods of classifying and cataloging, the artist proposes that scientific disciplines are not necessarily an accurate reading of nature, as they are also traversed by fiction, distorted discourses and constructed subjectivities.

On the other hand, in Hitos Deconstruidos [Milestones Deconstructed], the series of postcards reproducing famous sculptures, Diaz Cervantes interferes—through the physical elimination of fragments of the image—with the cultural discourses that categorize a simple object as a masterpiece (as in the discourse of cultural tourism, for example). In the series of collages Sin Título [Untitled] the artist formally employs an inverse strategy, for instead of removing pieces of the image, he decides to cover certain areas which leave a partial view of the animals or landscapes represented. Here, nature is "rarefied", hidden behind the representation or interpretation that is left.

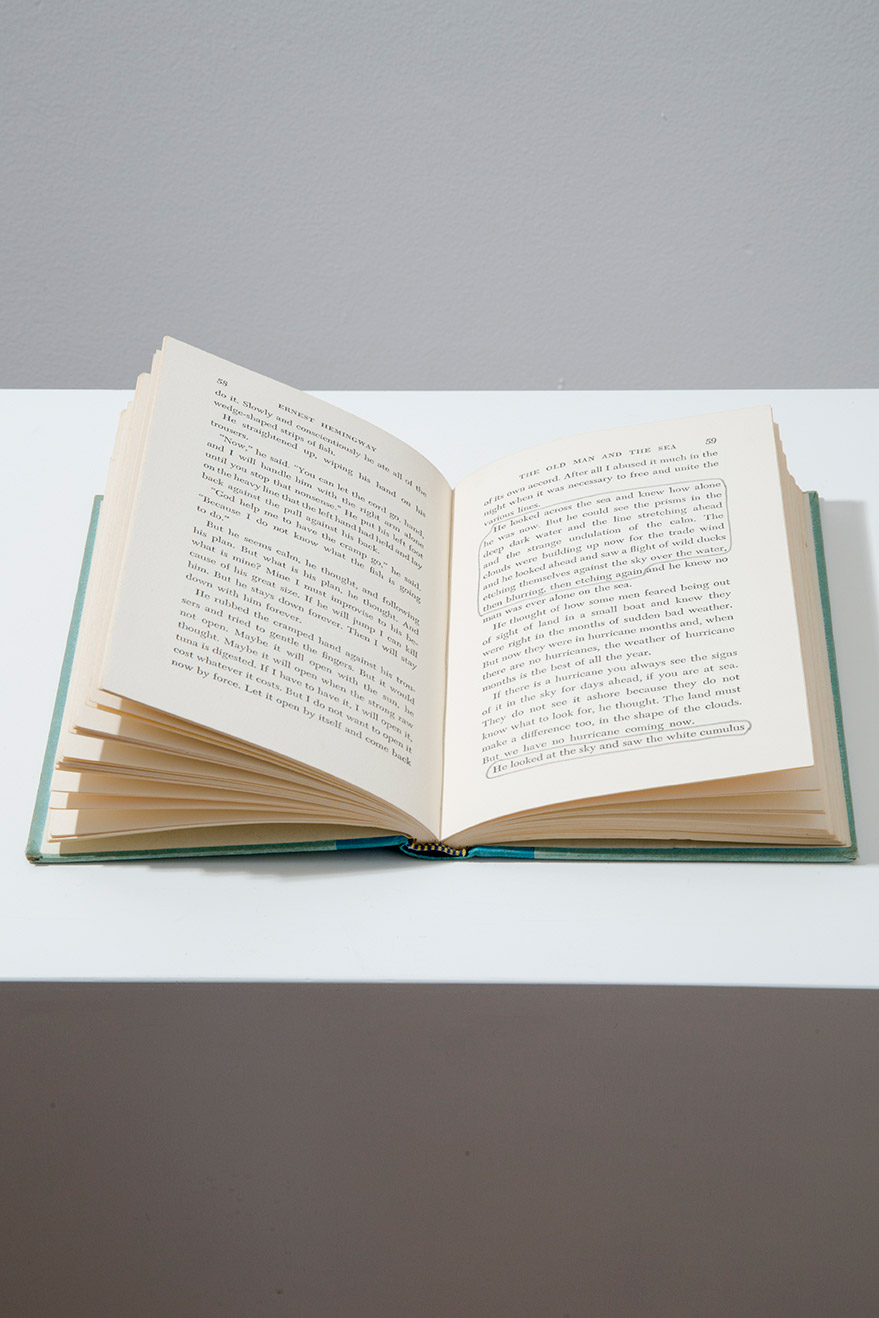

For his work, Paisajes Literarios, Francisco Ugarte identifies and highlights fragments of Ernst Hemingway’s “The old man and the sea” where landscapes or a moment of contemplation is described. This gesture, which draws attention to the visual characteristic of narrative, also urges us to think upon the construction of nature from what is seen or from what is written.

For Fragmentos Solares [Solar Fragments], Daniel Monroy Cuevas worked with images from books the artist chose, among other reasons, because all showed people or animals looking directly at the camera. Monroy Cuevas placed a mirror next to these selected images in order to photograph the geometric shapes resulting from the light and shadows at play. The technique uses the natural phenomenon of light to try to intervene in a space and time that once existed between the camera and the subject portrayed.

In Sin Título (100 ml de Agua de Rosas Pueden Perfumar el Danubio [Untitled (100 ml of Rosewater Can Scent the Danube)] Irizar "profanes" the river by pouring in it a bottle of rose water, while rhetorically questioning whether it is possible that a small gesture that interrupts a natural course, is capable of perfuming—or transforming—everything.

For Moving and absence, Israel Martínez uses recording material of locations where humans are not seen and that have substantial sound activity and overlays those recordings to images of sport venues and people doing various sports. Thus, the narrative is composed of sounds that do not strictly correspond to the images that are matched. The dislocation between visual and auditory sources causes that the resulting landscapes have a rare quality, almost mystical.

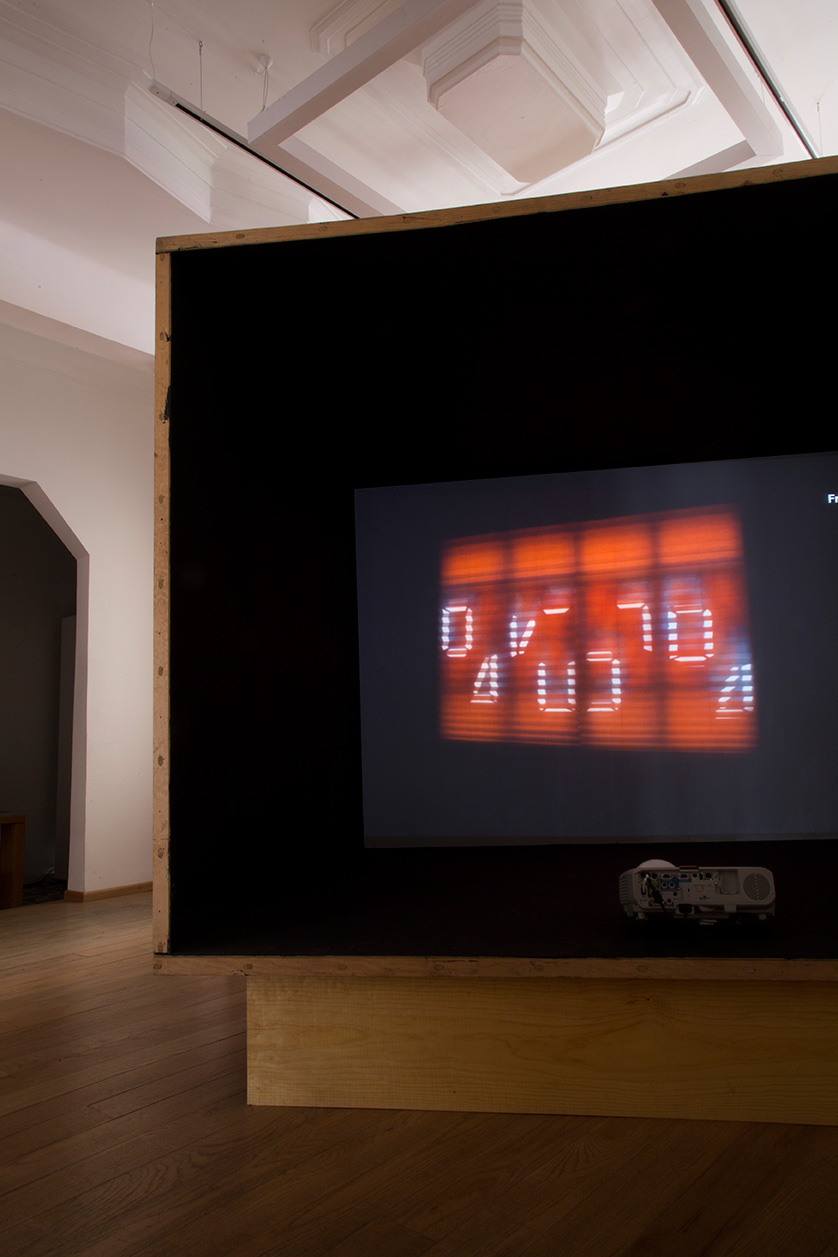

Finally, in Diablo Cazador de Hombres [Man-Hunting Devil], Daniel Monroy Cuevas refers to the science fiction movie Predator, where a digital clock with extraterrestrial "numbers" marks the time remaining before a bomb planted by the predatory alien ends the world. In his video, Monroy Cuevas reproduces these digits and displays them on some curtain blinds. His clock, however, counts frames per second, a measure used for images, particularly in video and film; a gesture suggesting that the time span created by these means is different from real time. The piece also manifests the apocalyptic character of all science fiction, whose narrative equates the near future to the image of a city in ruins, that is to say, the return to its primitive state, to the chaos of nature.

In one of Fitzcarraldo’s scenes in the film mentioned at the beginning of this text, the main character needs to get his boat to a remote river with difficult access. Fitzcarraldo decides that the easiest option is to cross by land, carrying his boat over a mountain, in order to reach the river. This act, as with many human efforts geared at ordering, conquering or interpreting the chaos of nature that we also form a part of, is both preposterous and poetic at the same time. It is probably not important to know whether Fitzcarraldo’s effort was successful or whether the action was doomed to fail from the beginning; for it is possible that the importance of this and of all attempts to signify the world through language lies in the fatuous and beautiful battle itself, constant and unanswered.

Bárbara Cuadriello