Untitled (the disappearance of the symbol)

Gold thread, pulleys, motor and steel structure

2015

In Mexico, the Phrygian cap was used as a symbol since 1823 with the establishment of the Republic and until the first half of the twentieth century. A symbol of freedom regained from the French Revolution and, at the same time, from the ancient world; when the slaves from Phrygia (now Turkey) were liberated, they would put on this hat, whose name derives from that particular geographical area. Fritzia Irízar takes such a significant image in the history of Mexico as well as all the Republican Latin American countries in order to discuss the construction and disappearance of the political symbols in the collective imagination. In this work Untitled (the disappearance of the symbol), a weaving machine undoes the stitches of a gold threaded Phrygian cap, causing the total disappearance of the object. This action triggers a series of meanings about the ideological fabrication between politics, economy and society.

In America, the Phrygian cap was mainly used in numismatics and heraldry and it represents an allegorical statement of republican freedom imposed by the new Nation States. In this sense, this is the result of an interest that is not born on the social sphere but on the political sphere. The different emblems where the Phrygian cap appears, such as in Mexican coins, show a nation in political transition goingfrom independence towards the constitution of the republic. Therefore, the geared sheaves (pulleys) used by the artist in her work, are understood as an apparatus that controls, manipulates and, at the same time, disappears the construction of symbols according to the political interests in turn. Moreover, the gold thread redefines the value of a symbol with a lost allegorical force. The Phrygian cap, never materialized before in the work of Irízar, is less of an iconographic study, it rather focuses on the possibility or impossibility of freedom. The absence of the object, sets the debate on democracy and the political machinery in motion behind the images and symbols that circulate through the repetition of history.

Untitled (Fake Nature)

Diamond

0.04 cm (0.02in)

2012

In early 2012, the Sierra Tarahumara suffered the effects of a drought - unusual for this region- that severly depleted agricultural plots and livestock. Public attention grew in response to a suposed wave of suicides within the Rarámuri community attributed to their unbearable poverty.

In an exercise revealing the absurd, diametrical distance in society, Irizar requested that members of the Rarámuri community donate their hair in order to produce an artificial diamond, created by extracting carbon molecules from human hair. The resulting crystal incarnates the contrast between the superfluous ambitions of a particular social sector- one that aspires to these symbols of wealth and can commission them as personalized objects-and the basic needs of a community whose survival hinges on conserving one of Mexico's richest cultural legacies.

Untitled (Meteorite)

Projection on screen and newspaper cut-outs

Variable dimensions

2012

The project is based in investigation of two similar events that ocurred in Sinaloa, one in 1863 and another in 2012: the discovery and impact of a meteorite. The first is the fifth largest metallic object on the world; the second hasn't been found.

The goal is to create a set of elements that trigger a conversation about an improbable phenomenon, allow us to daydream about the origin of these objects, and can be illustrated through imaginary reconstruction-as ultimately occurs at the end of its journey in the Sinaloa mountains, curently an impossible region to explore, an area on the verge of existing only in the popular imaginary.

The piece consists of newspaper clippings and a projecting that seeks to recreate the Bacubirito meteorite (discovered in 1863), building a space in which mass media, scientific research, and art converge. Their convergence, in turn, produces a complexity comprising the excesses, manipulation, accumulation, and dramatization of our immediate reality.

Untitled (Totem II)

Block of salt and documentation

55.9 x 139.7 x 27.9 cm (22.01 x 55 x 10.98 in)

2011

The block of salt (placed on a plinth) was exhibited in a white, luminous space that resembled both a space of spirituality and of science. The block of salt reminds us of a totem, which evokes faith, protection or spirituality, depending on the person watching. It also suggests the euphoric moment of adoration that turns into destruction, when people through rituals or ceremonies deteriorate the totem or even break off parts of it to keep these pieces as private relics.

Untitled (Totem II) allows the spectator to pay for a piece of the block that could be broken off and taken with them. Through this action, those myths related to bad luck (such as wasting salt) are challenged and the piece of the block becomes an element of faith that is kept as a relic. It forces the spectator to question the value of the common object versus the art-object and sets this question in a context of adoration of the market. The salt is given in a paper bag created by the artist. Each one is numerated, so people can keep it as part of the installation.

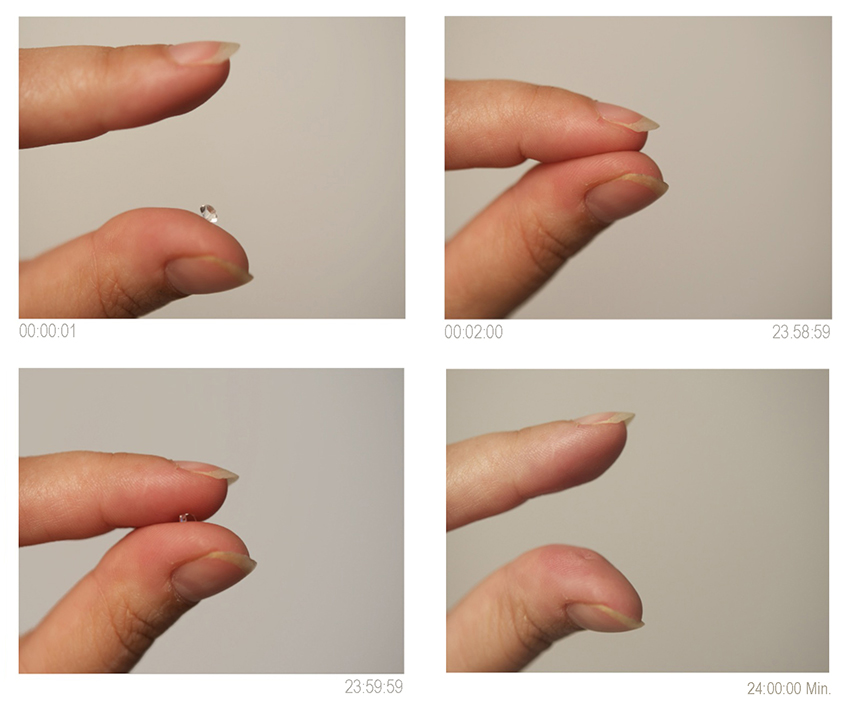

Untitled (4.81mm x 2.95mm,61.3%,.43ct,VS2, G)

Inkjet print

100 x 150 cm (39.37 x 59.06 in) cada uno

2008

A diamond, of the size and quality described in the title, is placed between the artist's fingers; she carries out her everyday activities, keeping the gem between her thumb and index finger for 24 hours. A selection of four photos, taken to document different moments of the action, testifies to the process - and to the incision the diamond leaves in her hand.

Untitled (Brute Force)

Photographs, video, sound and documentation

Variable dimensions

2010

In order to pique the curiosity of the common citizen, Irizar placed a safe in a public space in Mexico City, inscribing a mathematical equation on the surface - the solution being the combination to open the safe. The action combined the symbolic value of a specialized language, one marked by an aura of intellectual superiority associated with highly educated classes, with an object designed to be impenetrable, its presence implying the safekeeping of a valuable asset.

No other information about the safe was provided on site, so uncertainty acted as an added incentive to find out its contents. The safe was monitored 24 hours a day by a closed circuit surveillance system, transmitted in real time at the exhibition space.

A passerby's desires were thus confronted with two possibilities: engaging in intellectual effort or taking the contents of the safe by force.

Untitled (Proof of chance) [Madrid]

333 sacks each containing 3k of salt, 1 diamond and notarized document.

Variable dimensions

2010

The piece involves placing a ton of salt directly onto the ground; somewhere within the salt will be a real diamond worth at least a thousand dollars. This act is to be conducted in the presence of a notary public, who will atest to the diamond's authenticity. During the exhibition dates, 333 sacks sealed with security tape and weighing 3 kilos each, will be put on sale; the diamond could be found in any of these sacks. The piece continues when the buyer is notified in writing that the work will lose it's value as an artistic product if she opens the sack and breaks the seals, which means she must decide whether to keep it intact or try her luck by opening it.

Untitled (Time capsule)

Notarized document.

Variable dimensions

2008

Diamonds and salt are both crystals, similar in appearance, which have been considered valuable materiales over time. Salt was prized for its-food preserving properties and used as hard currency. By contrast, diamonds have been valued only for the purity of their appearance. The notions of these materials' value are subject to the beliefs and fantasies that lend the piece its complexity.

The work consists of a diamond in a safe filled with rock salt, which is then buried in a public plaza. The stone slab that covers the safe matches the rest of the plaza's paving, which impedes the piece from being discovered. A notary public attests to the events, so the only physical remnant of the piece is his notarial deed. The work transpires like a rumor surrounding the idea of a treasure hidden in an ordinary place. The public's desires and imagination come alive, circulating the action through their own storylines. The materiality of the work is replaced by the constructions of a myth.